The federal district court of Northern California, and perhaps eventually the Ninth Circuit, are about to decide a seminal case on child privacy in the internet age. It is a case that raises not only issues of national policy toward children and parental rights, but also issues of class action monitoring. For these cases require a kind of active monitoring not normally a part of judicial practice in common law jurisdictions. Courts in this country are structurally passive. They decide cases brought by contending parties. We assume that the proper precedent or ruling will come from the range of advocacy the parties provide.

Enter the abusive class action, with the current case of Fraley v. Facebook as Exhibit 1. This case was brought in name by the “class of Facebook” subscribers, including a subclass of millions of child-users aged 13 to 18. It seeks damages for alleged improper use of names and photos for a “sponsored stories” practice of publishing to one’s “friends” – a commercial endorsement of some sort – without effective advance consent. Facebook gets paid for it. Under the final proposed settlement now before the court, this allegedly unfair practice would yield the following financial terms: (a) a rather token system of less than $10 to each “claimant”, (b) possible awards to multiple consumer/privacy groups who might otherwise oppose it – as cy pres financial grants, and (c) $7.5 million to the firm for the class.

Besides these monies, what will be the critical court order dictating actual future practice? It first removes the reference to “prior consent” for the expropriation and sale of a Facebook members’ postings that was in the prior version of Facebook’s “terms and conditions.” Now it provides for the opposite, an explicit and blanket advance waiver of any compensation, and of blanket permission for ANY expropriation of ANY posting or photo put on Facebook – to be selected and arranged by it, with completely unfettered discretion. It applies to any member, including children. To repeat for the “that can’t be true” reader: Facebook can take any information posted, any photo, any combination, and repackage it, take money for it, and send to whomever it wishes, including potentially millions of recipients.

The limitations on this license are illusory. They include an alleged caveat that Facebook will respect destination limitation imposed by the member. But the “limits” to exposure of postings is not readily apparent and most importantly, the default value unless you act to change it, is “public” – no limitation. And nobody is now going to get any advance notice that such an expropriation will occur, know what it will consist of, when it will happen, or to whom it will be sent. Nothing. Nada. It just does it, as it pleases and to whomever it wishes. To be clear, this blanket advance waiver applies to any child who has not notified Facebook that a parent is also a Facebook subscriber, obviously the vast majority of kids. It purportedly constitutes advance consent (by a minor unable to enter into most enforceable contracts) without any notice in advance of a repackaging and publication, without any review or consent by parents, without any notice that it happened. You might learn post hoc, if someone tells you about it, but you will not know who got it. And anyone who gets it can copy and paste and re-transmit it to anyone else. And as with the internet in general, it tends to stay. It is not erased periodically.

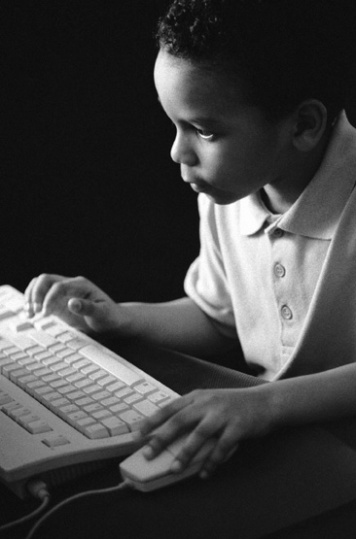

The public policy offense here is especially egregious for the children who will suffer this privacy incursion. Kids will have their postings sent in some unknown format and arrangement and purpose to – who knows? Regrettably, kids are not always completely mature in their postings, often intend for only a few to receive one, and suffer heightened emotional turmoil when they are embarrassed by the revelation to large numbers of unintended persons of something intended for private viewing, or perhaps better not sent at all. It is not an accident that California law requires children (not adults) to get parental permission for a tattoo. Parents are justifiably and legally in the proper position to protect and guide their children and that task is not best delegated in blank-check format to a third party commercial interest. But under the proposed final settlement, most parents will have no ability to monitor and limit their child’s on-line tattoo. They will not know about it, and they will not be asked.

This little “arrangement” between Facebook and the child “subclass” is hardly an improvement from current practice. It will take the form of a little missive in the middle of the adhesive “terms and conditions” sign off we all make without scrolling through the document. And this document has now been renamed the “rights and responsibilities” message and includes 18 detailed provisions in tiny print that requires 10 big scroll clicks to get through. This one will fit in under #10, after your fifth scroll down, mislabeled, and as Facebook well knows, unread by 99% plus of all new subscribers and 100% of all current subscribers (indeed, it is not even accessible from the member’s own existing Facebook page).

So, far from being “fair, reasonable and adequate” (required of class action settlements), this is a fraudulent remedy that is worse than the previous posture of the class (and particularly the subclass of children) prior to this suit. Indeed, the practice of expropriation that led to this suit and its rather transparently fake “remedial fund”– would be entirely approved were the new clause previously in effect. So instead of enforcing the law and obtaining both restitution and assurance of future compliance, we have a federal court being asked to officially approve future violations of the very type that brought the case before it.

And that is just the start of the problems here. On the minors side, we have especially egregious public policy offenses. This subclass of millions of children is in a different legal posture than are the adults. As noted above, children cannot agree to a contract of this sort. Facebook has stipulated that California law applies to its practices and this settlement. And while more than 17 states have similar laws, California has perhaps the clearest statutes requiring parental consent before any such privacy incursion can occur lawfully. The issue is addressed in Civil Code Section 3344 and in various sections of the Family Code. California’s Family Code statutes specifically address the illegality of a “delegation” to someone other than a parent or guardian of use of a child’s information/likeness.

So how does Facebook surmount these provisions in court? It actually argues with a straight face (an occupational necessity for attorneys) that the federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) entirely preempts all state law pertaining to child internet use and privacy. COPPA explicitly pertains only to children 0 to 13, and it prohibits Facebook and others from even allowing a subscription to any such child without prior parental permission. Nothing from such a young child may even be “captured” or “collected” by the internet entity. These children are (purportedly) not properly on Facebook at all, and its policy is at least facially not to accept them. So counsel actually stands up in court and declares that this high “floor” of protection directed only at children 0 – 13 means that all laws and protections for children 13-18 are extinguished. I kid you not, that is what they argue. And what case do they cite? The Arizona immigration decision holding that states cannot interfere with federal immigration policy. Really? Protecting children is hardly an occupation of the field by the United States government as are matters of national entry and citizenship. But that is the precedent cited.

But here is why this whole minuet playing out in the courtroom of Judge Richard Seeborg is so discouraging. The class attorney is asking for $7.5 million in fees, lead counsel asking for $980 for every hour he apparently breathes, with a multiplier. But it gets worse. Because one of the sections invoked in the case (Civil Code Section 3344) is a “fee shift” statute that requires unsuccessful plaintiffs to pay the legal fees of the defendant! So in every deposition of class representatives, Facebook attorneys, sounding a bit like minions of Al Capone, berate the class representative: “has your attorney informed you that if you proceed with this action and lose, you will have to pay OUR fees” (likely also millions)? And that examination went on at length for each of them! So… if you take Facebook’s convenient terms for future privacy gambolings the class attorney gets millions, if you persist and we win, we hit class counsel in the other direction – with our cost bill – and all of the class reps become bankrupt.

Now this is the setting for the proposal before the court. The tendency of most courts is to not appreciate the actual economic dynamics at play. It is tempting to get lost in the interstitial complexity of “how much should the class attorneys get?” and “should the class reps get $2,000 in incentive payments each or $5,000? Or is the notice adequate? Or, what if Facebook changes “Sponsored Stories” and calls it something else or does it a bit differently? [An irrelevant concern since the proposed final order allows it to go way beyond any “sponsored story” configuration.] But these questions dominated the hearing for final approval. Nor was the court told accurately that the lead class representative Fraley resigned from the case, citing their concern for “privacy” and the utter failure of the proposed settlement to provide it.

Courts, including this one, are hesitant to violate the traditional passive posture of judges, and to presume to second guess counsel and parties. The court here asked: “what is the difference between a minor and an adult who is the subject of a sponsored story reference?” And when reminded that children are in a different category, noted that “adults also” make imprudent posts. And, indeed, if all this case were about was Facebook saying that 13 year old Johnny or Mr. Smith “likes Big Macs,” maybe it does not warrant being the proverbial “federal case.” But, as noted, this order goes way, way beyond sponsored story license. It is an open book license. Kid postings are all clay for Facebook, with attribution, with widespread exposure and without prior approval of kids or parents. That is what this case is about. And it is also about the proper functioning of our courts.

In this case, we have suggested a simple change that is easy to do: Just have Facebook copy and paste what it intends to send out, add a description of the recipients, and send it to parents with an “I consent” button. If no parent has been identified or is available do not send anything. If the button is clicked by someone claiming in good faith to be a parent, send it. The court seems to view such an alternative as “interfering” with the parties and their arrangements.

But there are all sorts of alternatives possible that might create some bona fide prior consent. Nor is such a change a matter of “nit picking”, how can the present blank check delegation be “fair, reasonable and adequate” when it is overly broad, worse than the situation pre-litigation, and violative of the law?

This is a case where those critically affected are not really before the court. Often, objectors are looked upon as intruders, and they do sometimes have their own agendas. But, on the other hand, the class action mechanism has the flaw that only the courts can police – one manifested here in spades. You do not intervene on behalf of the state, and enter a court order sanctioning the violation of the common law, numerous statutes, privacy rights, child rights, parental rights – many of them with constitutional dimension. You best not do so with the rationalization that you are just mediating between two contending parties and what they propose is not only presumptively, but is dispositively, “fair, reasonable and adequate.”

About the Author: Robert C. Fellmeth is the Price Professor of Public Interest Law and Executive Director of the University of San Diego School of Law’s Center for Public Interest Law and its Children’s Advocacy Institute.